Stay vigilant, speak out against companies practicing deceptive design and use tech to help you out.

In this article we’ll cover…

About dark patterns and deceptive design

What are they?

Deceptive tactics in the online environment, more commonly known as “dark patterns” (and more recently as “deceptive design”), are methods websites and apps use to get you to do things you didn’t plan or mean to do, and which benefit the business. The term was coined by a UX expert Harry Brignull.

Deceptive design practices are based on making the pro-user or pro-consumer option highly inaccessible or inconvenient.

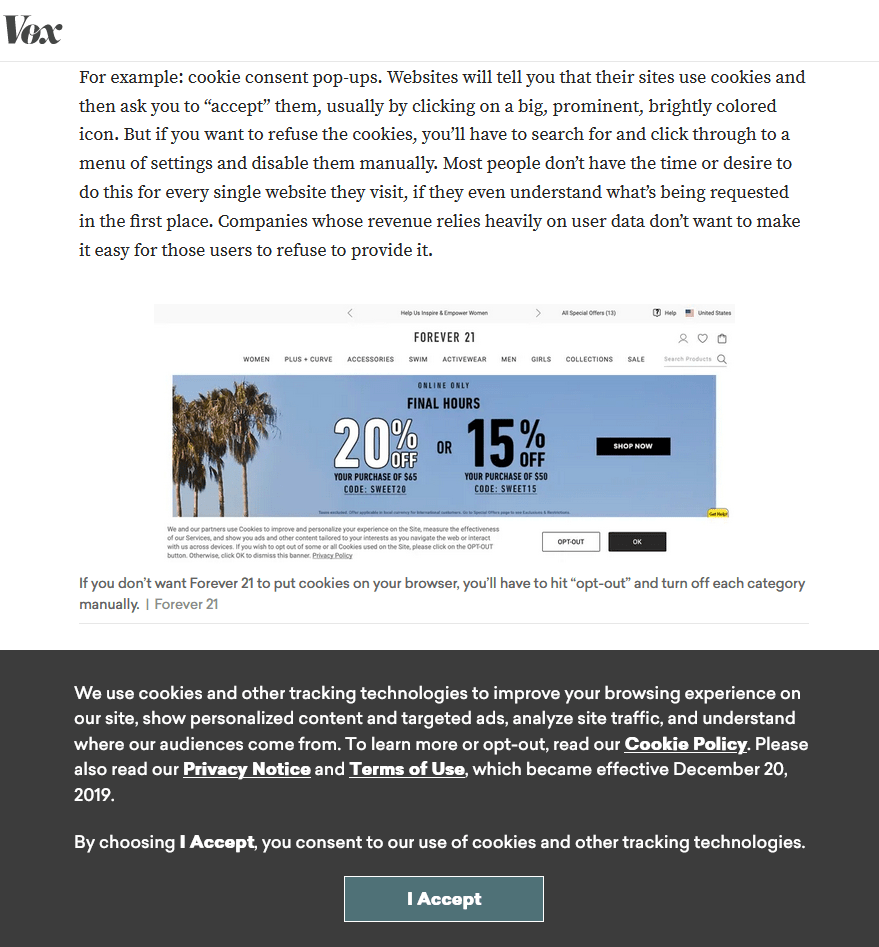

An example would be making the “accept cookies” a big and bright button, easily accessible, while “reject cookies” (if it’s even offered) would be hidden behind a different webpage, or the website would force you to uncheck a list of options and vendors manually.

Here’s an interesting example of Vox criticizing Forever 21 for their inconvenient cookie reject policy, while they don’t even allow any option for the user to opt-out. Not offering an easy opt-out option is illegal in the EU, which is where I was accessing this site at the time of writing.

Is anything being done about them?

Many laws, enforcement actions and statements have been announced, and some of them have managed to drive positive change, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (you can read the full history of GDPR here).

Most recently, the European Commission approved two more digital consumer legislation, the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA). Amazon was hit with €746 million in fines for violating GDPR, followed by the French CNIL hitting Google with €150 million and Facebook with €60 million in fines over cookie consent dark patterns in January 2022. As of July 2022, GDPR has resulted in over 1100 fines totaling over €1,6 billion. It’s a slow process, but it seems like companies are finally starting to take GDPR seriously.

In October 2021, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) announced a new enforcement policy “against illegal dark patterns that trick or trap consumers into subscriptions”, outlining that using deceptive strategies to mislead users into subscriptions would be against the law. The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) was passed in 2020, as an expansion of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which is supposed to take effect from 2023. You can lead more on dark pattern regulation here.

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) announced an enforcement action in early 2019, aiming to secure change in the online hotel booking space operating in the UK, which relied heavily on high-pressure selling tactics and various dark patterns in order to make sales. Major booking websites were the subject of the CMA enforcement action, including Expedia, Booking.com, Hotels.com, Trivago, and others. Later in the year, 25 more companies, like Google, AirBnB and TripAdvisor, also agreed to make formal commitments to change their selling practices.

However, the main issue has been getting companies to follow through and actually make significant changes. Various governmental bodies are continuously revising, updating and enforcing, but it’s a slow race.

Are dark patterns worth it long-term?

Companies use dark patterns to guide (or force) users into behaviors that benefit the business, not the users. Depending on the type of product or service, they may be effective for driving profit.

An example would be an airline that the traveler has to take, because there is no other competitor that goes through that exact route. That way, the customer is “forced” to go through the booking process filled with avoiding add-ons and expensive upgrades the airline hopes you choose by accident.

Same applies for social media giants, since many people have a hard time leaving social media because of their friends and family.

However, while these types of deceptive tactics might drive short-term gains in the form of micro-conversions, the company may be causing a long-term loss in its credibility and brand.

A 2015 study showed that deception in advertisements was associated with “lower levels of perceived corporate credibility, less favorable attitudes toward the ad, less favorable attitudes toward the advertised brand, and decreased purchase intentions toward the product in the ad”.

A literary review of 2018 identified that studies included in the review show overall negative outcomes even for perception of deceit – lower likelihood of recommendation and repurchasing, and a general distrust of the brand.

What’s more, the real question is the quality of leads that these tactics produce. User intent is an extremely important element to online marketing and lead generation.

Even if you manage to pressure your user into sharing their email address, you may just end up in a spam folder and/or your open and click-through rates would be lower, which doesn’t help drive the business forward.

Types of dark patterns

Here are some examples of the deceptive tactics websites and apps use to deceive or pressure you into doing things you didn’t mean to.

This is by no means an exhaustive list, and you can find more examples on Harry Brignull’s website. I also recommend following the Deceptive Design Twitter account if you want to see various company-specific examples of dark patterns.

Difficult to cancel subscriptions

Subscription cancellations are some of the most notorious

Many companies today have embraced the “give us payment info to activate free trial” model of luring customers to convert, and hoping that they forget to cancel their free trial before the payment starts.

Once this happens, the customer either forgets about the subscription altogether, or they’re faced with an extremely inconvenient stream of hoops they have to jump in order to unsubscribe.

Some companies, like Amazon, have notoriously long cancellation processes consisting of several pages filled with dark patterns. Thankfully, Amazon has changed its cancellation process in the EU recently, according to the report by the European Commission on July 1st, 2022. Unfortunately, this change doesn’t affect users outside of the EU as of today.

Other companies force you to jump through many steps that don’t just involve navigating multiple pages with a purposely terrible user experience.

For example, The Economist, arguably one of the most influential economics newspapers in the world, has an abhorrent system for cancelling subscriptions.

Once you’ve navigated their website (not the app) for the cancellation button and entered the reason why you’re canceling, you’re told that you have to get in touch with their agent in order to cancel, either through a chat or via phone call.

Then you’re put on hold, and have to wait approximately 20-30 minutes to even get in touch with the customer service. Once they finally reach out, you’re forced to deal with 30ish minutes of gruesome hard-selling of discounted versions of the subscriptions.

There is an excellent thread detailing this process with screenshots. You can take a look at it here.

You only need to take a second to look at their TrustPilot page to get an idea of what you’re dealing with: 518 reviews with an average of 1.5, and 60% being a 1. Needless to say, this is an awful way to treat users, and will likely cause them to distrust the company in the future.

Being shamed into confirming

This manipulative tactic is used to guilt-trip you into purchasing or signing up for something that you don’t necessarily want. Usually, the company is requesting that enter your email address, add an extra feature to the cart, or turn off ad-block.

They give you a large bright button to accept their request, while the ‘no’ is usually in a much smaller font. Moreover, it’s worded in a very calculating way, such as that it would go against what most people consider “common sense”.

That way, the user is forced to pause and think about the negative “consequences” of rejecting the offer. These could be in the form of a loss on discounts,

You can see more examples here.

But is shaming users into agreeing to give out their email or to buy an item worth it? While they might drive a short-term gain, the long-term effects tend to be more negative.

A 2015 study showed that the deception in advertisements were associated with “lower levels of perceived corporate credibility, less favorable attitudes toward the ad, less favorable attitudes toward the advertised brand, and decreased purchase intentions toward the product in the ad”.

Difficult to delete accounts and the data

Deleting accounts is a hassle more often than not. This is because companies profit off your data, and it’s in their interest to keep you (and your data) around as long as possible.

If you’ve ever attempted to delete an online account at some point, you might’ve encountered one of the following scenarios:

- There is no such option

- It’s technically possible, but there is a large roadblock

- It’s possible with some extra steps

- It can be done in a few clicks

One example of deceptive practices in account and data deletion would be Facebook, which keeps some data even after the account is deleted.

They claim this is due to legal obligations, which is understandable, but some of it is a bit more vague, such as to “promote safety, integrity and security in limited circumstances outside of the performance of our contracts with [the user]” (taken from their Privacy Policy).

In a table quite obviously formatted to obscure readability, they name a long list of the type of information they can keep for this purpose. Among others, this data includes:

- Content posted on the platform

- Content you provided through the camera feature, your camera roll settings, or through the voice-enabled features

- Metadata (date of the content shared, location of the device, device ID…)

- Types of content you view or interact with, and how you interact with it (how long you look at it, if you leave a like, etc.)

- Apps and features you use, and what actions you take in them (they didn’t specify the source, but presumably on Meta platforms and outside of them)

- Purchases or other transactions you make, including truncated credit card information (once again they didn’t specify the source, but certainly on Meta platforms and possibly outside of them)

- What you’re doing on your device (like whether a Meta-family app is in the foreground or if your mouse is moving)

That is a long list of information that Facebook can keep even after you delete your account.

Of course, while Facebook is pretty notorious for its data handling, it’s not the only company with inconvenient or borderline problematic approach to account deletion.

For example, Wikipedia, WordPress, and don’t allow you to delete your accounts on those platforms. Scribd doesn’t let you delete your account until your subscription/free trial expires.

There is an excellent website that serves as a directory of direct links for account deletion, called JustDeleteMe. It also color-codes the websites according to how difficult it is to delete an account on that platform.

If you live in the EU, you can file a request for your data deletion to individual companies under Article 17 of GDPR, also known as “Right to Erasure” or “The Right to be Forgotten”.

While there are some exemptions and not all companies honor the request, it’s still worth the try. This is the official request template. Google has its own form, which can be found here. If you would like to more about Google data deletion under GDPR, you can read it all in this guide.

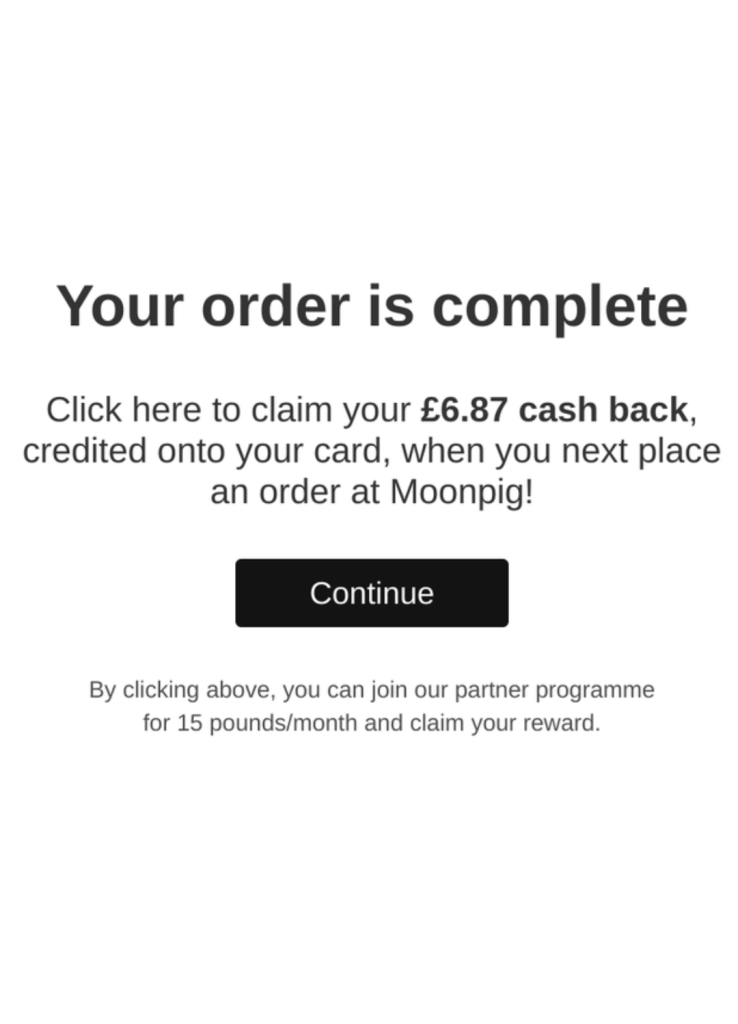

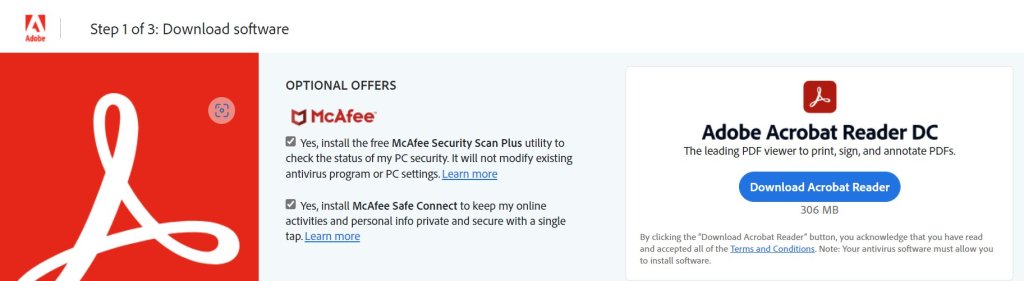

Confusing agreements

These usually come in the form of double negation, confusing wording or misleading buttons. The intent is clearly to obfuscate the meaning of the button or tick-box that the user is supposed to click, and to (mis)guide them into choosing the option that the company wants.

Fake scarcity

Fake scarcity refers to many sales techniques that are used to instill fear into customers and users, and which lead to conversion (in the form of sign ups, purchases or downloads). These include but aren’t limited to:

- Countdown timers that run on a loop

- Fake discounts (when the “initial” price was very high so the “discounted” price seems like a bargain)

- Continuous pop-ups about all the other people that are (apparently) looking at the same product you’re looking at, or who just bought it

- “Only X number of products left!” stickers.

Many e-commerce websites use these dishonest techniques to drive sales purely based on FOMO (fear of missing out). Booking websites are particularly infamous for this.

General tips on how to avoid (and fight back against) dark patterns

The internet is full of dark patterns because they work.

While governmental bodies are trying to catch up to the ever-changing world of online marketing, we as users need to stay vigilant and keep calling companies out for their shady practices.

1. Learn more about dark patterns and your rights

This article is a good start, but you should keep yourself informed about various dark patterns, which only continue evolving over time. Tricks that used to work before may not be as successful now, and companies might’ve thought of new ways of tip-toeing around regulations.

That’s why it’s important to stay up to date and refresh your knowledge from time to time.

Similarly, try to learn more about your local regulations for dark patterns. Talk about them and spread awareness. Reach out to your local governmental bodies and try to start a discourse about what can be done.

2. Stay vigilant and level-headed

Staying vigilant doesn’t have to mean “never relaxing” around technology, but it does refer to keeping a certain level of mindfulness around your tech use.

For example, if you’re browsing blogs about a topic you’re interested in, and a cookie banner pops up that doesn’t let you opt-out of cookies, pause and ask yourself “do I really need to use this website?”, or “does this page truly provide enough value for me?”.

If the value is truly there, then proceed. If not, try to find another source for what you’re looking for. There are more websites and apps out there than you could possibly go through.

On a similar note, try to keep calm when you’re faced with some dark patterns that are meant to stir you up, like fake scarcity.

These types of sales techniques exploit our innate fears, so keeping calm is crucial in order not to be taken advantage of.

3. Use a private alternative

You should take advantage of the many private alternatives and proxies to common websites and apps you use whenever you can.

Private alternatives also often bring other benefits like faster loading times and no ads, but sometimes at the cost of not being able to post or like things.

Here are some private alternatives to popular web uses:

Blogs and websites

- RSS feeds: RSS (Really simple syndication) is basically an accumulation of all the relevant content on the page, without ads and unnecessary distraction.

- Simply download an RSS reader of your choice, or use a web-based one, and you can read/watch content from various websites and social media without even having to access them.

- Nitter (web front-end): clean interface, and the website allows you to follow account RSS feeds, which means no repetitive searching.

- Mastodon (alternative to Twitter): it’s a different social media app that looks like Twitter, but it’s decentralized.

YouTube

- Piped (web front-end): simple to use ad-free front-end for YouTube.

- FreeTube (PC client): allows you to subscribe and watch videos ad-free without even having to use the browser.

- LBRY and Odysee (alternatives to YouTube): different websites for sharing videos.

4. Fight tech, with tech

There are various pieces of technology that can help in dealing with dark patterns. Consider using some of the following to reduce the risk of being tricked and/or exploited.

Aliasing tools

Avoiding dark pattern pitfalls is seemingly a never-ending battle, and companies hope that you will get fatigued from saying no and simply give up.

Alternatively, you might genuinely be interested in what the website offers, but you don’t want to be bombarded with their promotional email. In these cases, you should use aliases and temporary profiles to avoid spam.

- SimpleLogin/AnonAddy: replaces your real email address with an anonymized alias, so that the company doesn’t have your real personal information. You can disable aliases when you want to stop receiving emails.

- Privacy.com, Revolut and other temporary virtual cards: allow you to create aliases of your real bank info, so that companies can’t keep charging you after you’re done using their services. Just like with emails, you can disable these temporary cards as well.

- Apple’s Hide My Email feature (iOS/iPadOS 15 or later).

Search engines

Private search engines are not filled with paid advertisements that look like search results. They also don’t track how or when you look and click on a link. These are the easiest ones to switch to:

- DuckDuckGo (Bing results)

- Startpage (Google results)

- Brave Search (unique results)

You should also consider using multiple browsers for different purposes. This is not only good for dark patterns, but also for general browsing “hygiene”.

Browser extensions

Browsers are getting more and more advanced settings these days so that there is not much need for too many extensions.

Adblockers and tracker/cookie removers help prevent websites from tracking you across the internet, which is one of the main ways companies build profiles and exploit your search history.

These ones are always good to have, and won’t affect your day-to-day experience:

- uBlock Origin: blocks ads and website trackers.

- Decentraleyes: protects you against tracking through “free” and centralized content delivery.

- Bitwarden: password manager that helps you remember login details and create strong passwords so that you don’t reuse the same ones.

If you’d like to go a little bit more advanced, you can download the following two:

- Cookie AutoDelete: deletes all cookies upon closing of the tab. You can do a similar thing directly from Brave and Firefox settings.

- CanvasBlocker: prevents websites from fingerprinting via some JavaScript APIs.

- NoScript [super-advanced users only]: blocks all JavaScript. This will render most websites unusable. You can also do this directly in some browsers without the extension.

Leave a comment